I was born into a life of privilege. That is, to say wealthy and white. And I used to be unaware of it. In this naïveté, I was blind to the world outside of my suburban neighborhood—which was, and remains, one of the wealthiest in San Diego. Perhaps it was simply that I never really left my locality: the public school I attended was five minutes away from where I lived, and the Little League baseball games I played in were at the fields at my elementary school. For groceries and errands, we often did not have to go too far out of our community (and when we did it was often to a neighboring suburb). It was not until I was a teenager, as I began being exposed to the world outside of my suburban bubble, and learned about the historical factors that led to me having this privilege.

Rather ironically, I began discovering this privilege during my time at a fairly homogeneous wealthy and white private high school. I think that this can be attributed to a couple of factors in particular. For one, the depth to which I was learning about history and social studies shifted. After several years of learning history in a rather shallow context, my teachers forced me to dig deeper into the rationale and consequences of actions taken by people in the past. Often, this revealed race-based factors—typically whites trying to assert themselves as a superior race.

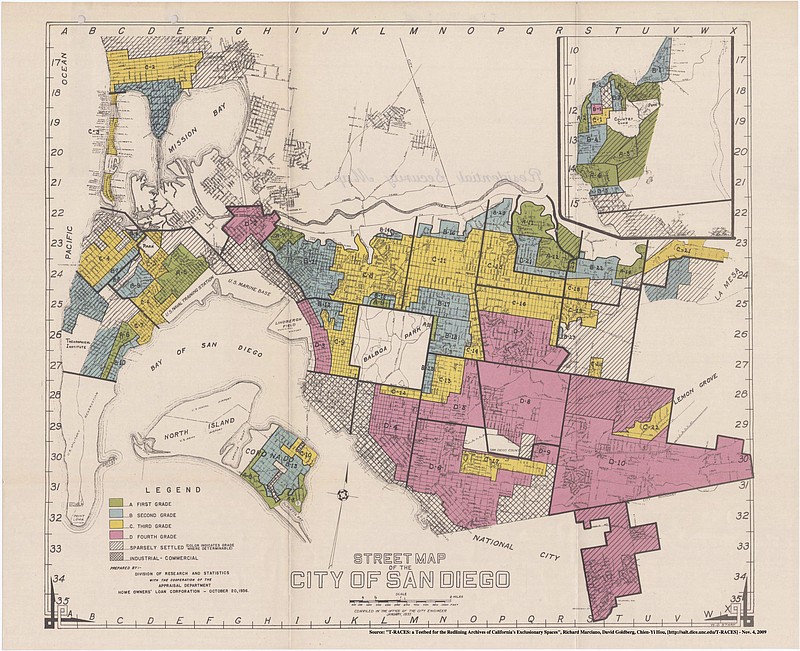

For example, the first time I had heard about “redlining,” or the appraised value of homes back in the 1930s based on the neighborhood they were located in, was during my sophomore year Global History II class. Previously, I had thought of discrimination as something that had been limited to the southern United States. I learned very quickly that this was not the case. The teacher showed us a redlining map from San Diego (included on the right), and some things immediately stood out. For one, many of the neighborhoods shaded in green or blue on the map (the higher appraisal neighborhoods) were, and remain wealthier and whiter. On the other hand, the areas shaded in yellow or red (the lower appraisal neighborhoods) were areas with lower income and have higher minority populations, and remain that way in the present. As I came to learn, this was not just a coincidence. In order to further segregate these communities, those appraising home values intentionally gave those living in white neighborhoods more favorable appraisals (increasing wealth in these communities), while giving those living in non-predominantly white neighborhoods less favorable appraisals (decreasing wealth in these communities). In turn, this increased the wealth gap between neighborhoods, making it more difficult for people of color to move into white neighborhoods. This, by and large, explains why the neighborhood I live in remains white and wealthy to this day.

Source: https://www.kpbs.org/news/2018/apr/05/Redlinings-Mark-On-San-Diego-Persists/

What I had yet to realize was the tremendous impact wealth has on a community, and the ability of those living there to acquire more wealth. As I have come to know now, the quality of one’s education plays a large role in their future access to wealth. However, quality of education, particularly in public schools, is often tied to the wealth of the community the school is located in due to funding coming from property taxes. I attended a public elementary school recognized as a “California Distinguished School,” meaning it had some of the highest standardized test scores of any public elementary school in the state. Here I had a high quality of education: small class sizes, great teachers, and extracurricular classes (PE, art, music, science lab, and computer lab).

Even with the elementary school I went to being in one of the wealthiest suburbs of San Diego, there was a period of time during the recession where it struggled to keep some of these extracurricular programs running. It was fortunate enough to have them in the first place, namely due to the school district being located in some of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the county. Small class sizes played a large role in my learning as well, and the school could afford more teachers to keep the classes small. Thomas Shapiro writes in Toxic Inequality: How America’s Wealth Gap Destroys Mobility, Deepens the Racial Divide, and Threatens Our Future that “[a] family’s income reflects educational and occupational achievements…” (24). Without this funding, the overall quality of education would likely have been lower, and thus the likelihood of me reaching the educational achievements Shapiro describes would be lower as well. Due to the decreased funding of schools in lower income neighborhoods, students in these areas have a decreased chance of reaching these achievements. As a result, the quality of education I received at the public elementary school was largely tied to me living in a high income neighborhood. Had I lived in a lower income neighborhood, the quality of education would likely have been worse, and thus it would be harder for me to reach educational achievements.

As I mentioned earlier, I attended a private school for middle and high school. Had it not been for the wealth my family has, I probably would not have been able to have this opportunity. This is another example of how access to wealth can impact the quality of education one receives. A large portion of the students at the school came from a similar background—albeit from other wealthy, white suburban neighborhoods from around San Diego. The decision to go to private school made educational achievements even easier to reach, as the quality of education was even higher, largely due to the smaller class sizes. In high school, Advanced Placement and honors courses were almost seen as standard, and the classes I took prepared me for the workload associated with college. All of my high school classmates chose to pursue some form of higher education, whether it was in the form of a community college or a four-year institution.

Growing up in a wealthy, white neighborhood has afforded me an advantage over millions of other Americans. This advantage makes it more likely for me to be wealthy in the future, and is a result of where I grew up. Living here has allowed me to receive a higher quality education, and allowed me to pursue higher education at a liberal arts college. The ability to pursue higher education has raised my chances at having a high-income job in the future. As a result, I have a good chance at remaining wealthy in the future. Had I lived elsewhere, many of these opportunities would have not been afforded to me, and the likelihood of me being wealthy in the future would be significantly decreased. Unfortunately, this is the reality for millions of Americans, and will be, until the wealth gap is narrowed.

A frank admission, and the illustration of redlining where you grew up helps make the context very clear.